On February 15, 1995, arguably the most notorious and first hacker cover boy, Kevin Mitnick, was apprehended in Raleigh, NC. Charged with crimes ranging from wire fraud to unauthorized access to a federal computer, there was a distinct possibility that he would spend the rest of his life in jail.

So, what made Mitnick’s approach to hacking, so unique and prolific? He consistently exploited weaknesses in a company’s technology, similar to other hackers, but more effectively, he used social engineering to gain access to practically any system he wanted. Essentially, he capitalized off of human error.

He would end up only serving five years of his sentence, due mostly to the fact that he never gained anything, money or influence, through his series of hacks. However, after his time in jail, he would go on to form a computer security company — because who best to help companies overcome the serious threat of hackers — than a former hacker himself.

Like a modern-day Art of (Digital) War, "To know your enemy, you must become your enemy." We had this mentality in mind when we created this article on fraudsters. Whereas Kevin Mitnick was a hacker anomaly, never proven to have stolen anything, today’s fraudsters are driven by a solitary goal, money. In order to beat the fraudster, it’s important to think like one. Here’s how to hack it as a fraudster in just a few steps:

Step 1: Master the underground

Ad fraud, also referred to as "invalid traffic" or IVT by the ad industry, is a continued and complex challenge that we face today. As estimates for ad fraud reach upward, costing the industry around $16.4 billion globally this year, larger fraud issues with extensive coverage in the news media — like bots infiltrating our social media platforms, click farms, traffic-driving "clickbait" sites, and the ever-growing list of company hacks and data breaches — have placed higher scrutiny and amplification on the issue. However, advertisers are now better armed to more actively identify malicious activity through the use of ad verification technology, which ensures that ads appear on intended sites and reach the targeted human audience.

Invalid traffic is when legitimate ads are served in an environment that will never have the ability to be seen by a human. The Media Ratings Council (MRC) has categorized IVT into two buckets — General Invalid Traffic (GIVT) or Sophisticated Invalid Traffic (SIVT):

• GIVT refers to non-malicious forms of non-human activity, including spiders and crawlers used by companies like Google. The IAB keeps track of these already known spiders and bots and updates this list monthly. Although not malicious in intent, media serving to GIVT still results in media waste as the impressions are not served to a human.

• SIVT, on the other hand, refers to more sophisticated forms of invalid traffic. This category includes the ever-evolving malicious bots, malware installation, hijacked devices, and nefarious sites utilizing ad stacking (placing multiple ads on top of each other within a single ad slot) or pixel stuffing (serving one or multiple ads in a single 1X1 pixel frame). Due to rapid evolution to avoid detection, this form of invalid traffic is responsible for stealing the majority of advertising dollars.

Step 2: Lock your target

The main objective for any fraudster is to steal as much as they can in a very short window of time before the operation is detected and shut down. Ad fraud is no different. From desktop to mobile, display to video, all devices and ad inventory are susceptible to invalid traffic.

Premium inventory, such as in-stream video, is currently at the highest risk of fraud because the ad value is high. In the case of video, it is also harder to identify and remediate in this space because tracking standards are often not followed. The overall video IVT rate for all types of buys in the U.S. is around 13.7% according to Integral Ad Science’s (IAS) Media Quality Report for 1H 2017.

Step 3: Plan your heist and assemble your (robot) team

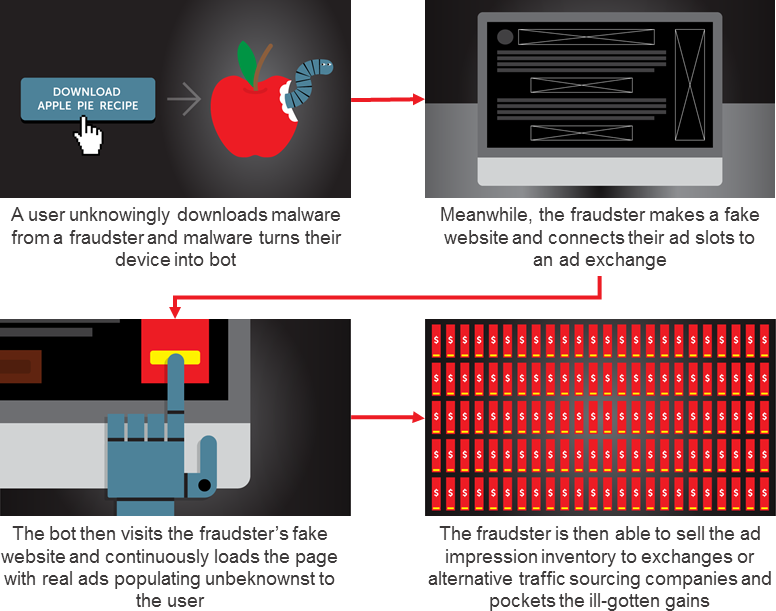

Even naïve or lesser-informed people know that emails from a Nigerian Prince promising fortunes aren’t worth opening. But over time, fraudsters are continually evolving their game to cheat a savvier audience. Now fraudsters use bots to commit ad fraud, installing them on unsuspecting users’ devices via malware. Bots are “robot” computer programs that are created by fraudsters to accomplish a variety of tasks, including continuously loading web pages that simulate a real human browsing the web or using an app.

A fraudster’s ability to make money can be tied to the scale of their operation. One way they can achieve this scale is through creating a botnet, which is a network of devices infected with malicious bots controlled by the fraudster.

Bogus coupons, fake vacation giveaways, and mal-intentioned pop-ups housing computer viruses are designed to drive users to click, share personal information, or download fake virus protection — all ways users unknowingly download malware to their devices.

A user who accidentally downloads this malware thinks they are only scrolling through Facebook, but without being able to see it, a bot has opened their web browser in the background and their device is continuously calling the fraudster’s fake website. This can result in a user loading thousands of ads that are never even seen — and the user has now become an unwitting accomplice.

There are various types of bots within the digital landscape used to commit ad fraud, and fraudsters are constantly looking for innovative, unidentifiable ways to siphon ad revenue. New or evolutions of existing bots are constantly being developed to avoid detection. According to IAS, below is a list of the most common bots known today:

• Standard bots – Includes common strains of Internet Explorer-based malware, primarily on residential computers. Focuses on scale rather than compiling cookies or evading detection.

• Volunteer bots – Resides in cloud services, allowing 24/7 operations and eliminating machine load time. Implements basic detection-evasion measures such as user agent spoofing. Most popular within the U.S.

• Nomadic bots – Uses proxy servers or VPNs to hide the network location. Difficult to track with typical user identification techniques. Frequently associated with European IP addresses.

• Sitting ducks – Resides on end-user devices. Detection avoidance pursued through aggressive use of traffic-filtering services falsely claiming to defeat fraud prevention services.

• Profile bots – Focuses on developing valuable user profiles by spending time on premium sites. Evades detection through user agent spoofing and use of public proxy servers; often web kit-based.

• Masked bots – Goes to great lengths to evade detection and obscure activity. Numerous browser environment aspects are manipulated. Premium publishers face two dangers as bots build user profiles and also perform domain spoofing.

Step 4: Rake in the dough

One common method fraudsters use to make money is sending their botnets to fake websites they’ve created, which are monetized through legitimate advertising. The trouble for advertisers, however, is that no humans actually see these ads since the infected devices are visiting the site and loading ads entirely unbeknownst to the user.

Fraudsters have been profiting from invalid traffic for a while, but have been able to further boost their ill-gotten gains by sourcing advertiser demand from ad exchanges in recent years. Fraudsters connect their ad slots to ad exchanges like a normal publisher would, and then use their botnets to continuously load these web pages to create millions of actual ad impressions. The fraudster can then sell this impression inventory from their fake websites (again, ads that are never seen by humans) to the ad exchange or to alternative demand sourcing companies on a CPM basis and pocket the dough. And because of the open nature of many ad exchanges, this fraud often is more difficult to detect and stamp out.

Fraudsters also can make money by selling their bots on the dark web. This happens by using exploit kits, which are malicious toolkits containing various ways to deliver malware with high success rates. They are advertised to other cyber-criminal resellers who have the option of renting the kits, ranging from ~$30 to $500, for anywhere up to a month. These resellers can then hike up the prices further and sell to a plethora of additional fraudsters. Often, fraudsters can make upwards of $100K a week from the exploit kit rental fees.

Joining the Good Guys

The good news is, as fraudulent bots and publishers get more sophisticated, so do we. Whether through personal anti-virus software for individuals or enterprise ad verification suites for advertisers, there are heroes already out there fighting against fraud. Now that you know how to think like a fraudster, here are a few techniques for minimizing the impact of ad fraud:

• Know the warning signs. If it looks too good to be true, you’re probably right. Conversely, if your performance metrics look extremely low as compared to other channels, this should set off a red flag. Know the warning signs and continuously monitor your performance data to help detect suspicious activity. Watch for abnormally high click-through rates (CTRs), suspicious page views per session, low time-on-site, high bounce rates, disproportionate impressions on older browser versions, or no performance altogether.

• Rely on meaningful engagement metrics, and terminate traffic with below-average or suspicious performance. Views and clicks are among the easiest actions bots can take, so campaigns that rely on impressions or CTR for optimization are at much higher risk of falling victim to fraud. Engagement metrics like time-on-site or lead form completion will be a stronger indication of real human activity.

• Maintain universal exclusion or inclusion lists. Some sites deliver a higher majority of fraudulent impressions. Fraudsters try to outsmart us by making it seem like purchased impressions are coming from a trustworthy site, using URLs that may seem believable, to sites like www.hufffingtonpost.com. Didn’t catch the mistake (3 f’s)? It’s intended that way. By blocking sites you’ve already detected as suspicious using an exclusion list, you can ensure your ads will not be wasted there moving forward. However, many marketers feel this is not good enough, knowing as soon as one site is blocked, fraudsters just spin up new URLs to replace them. Inclusion lists, on the other hand, are often a better route for marketers who want to restrict their ad placements to only run on sites they have deemed trustworthy.

• Use the effective tools at your disposal. Those who put the right tools and practices in place will limit their campaign’s exposure to ad fraud. Onboarding anti-fraud tools that are MRC accredited can help to detect and block fraudulent activity at the pre-bid level.

• Get involved. We all must do our part to fight the good fight against invalid traffic. Join Omnicom Media Group’s efforts by getting involved in groups like TAG (Trustworthy Accountability Group), which is a joint marketing-media industry program stemming from the American Association of Advertising Agencies (4A’s), Association of National Advertisers (ANA), and the Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB). TAG works with players across the supply chain to eliminate fraudulent traffic, combat malware, fight internet piracy, and promote transparency.

• Partner with a subject matter expert who can navigate the ins and outs. Knowledge is power, and the complexities of the industry require skilled expertise from years of experience. Additionally, fraudsters have realized that there is way too much money to be made, so as the industry develops consistent best practices, they’ll simply institute new techniques and approaches to fraud. This means that it is crucial for brands and marketers to surround their business with digital specialists who understand how the entire ecosystem works, better setting themselves up for success.